Why we care about ‘forever chemicals’ and why you should too

PFAS have been used in consumer products since the 1940s. They are extremely persistent, build up in the environment and some also in our bodies. This is why they are often called forever chemicals. Tests indicate that some cause serious health effects such as cancer and liver damage. The good news is that the EU is taking action to reduce their use.

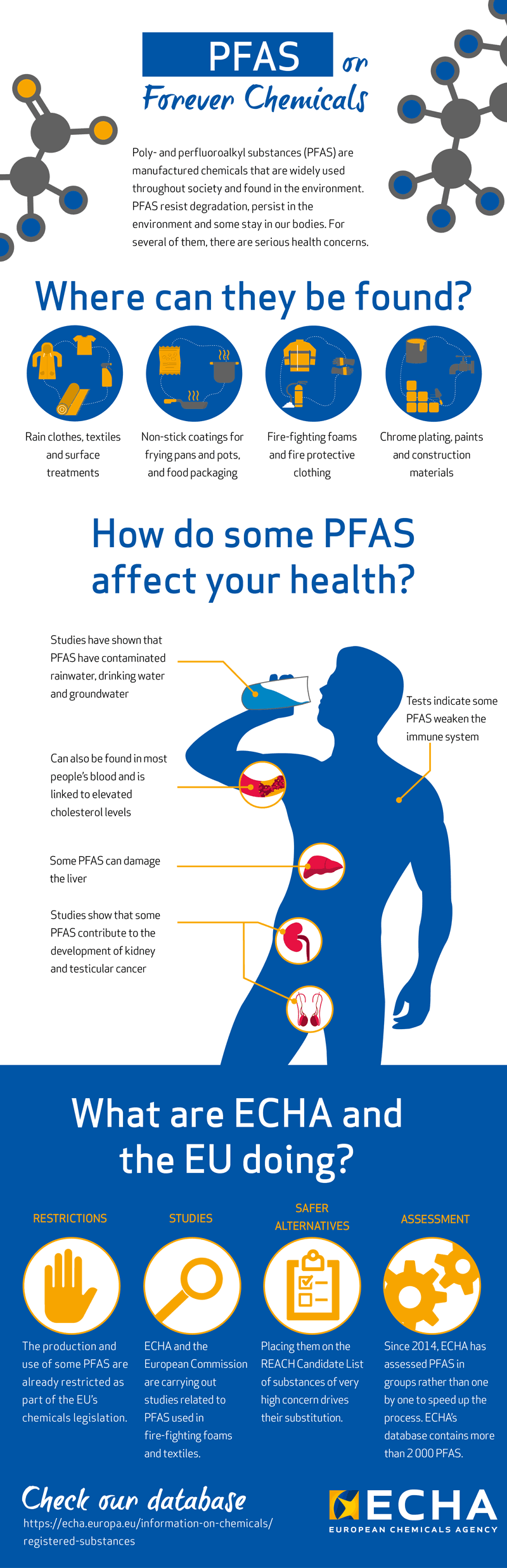

You may never have heard of them, but there is no doubt that you have been in contact with poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances – PFAS for short. They are manufactured chemicals and are so widely used by industry and to produce consumer products that they have been discovered in rain water, drinking water, ground water and, some of them according to biomonitoring studies, also in the blood of European and American citizens.

The problem is that there are serious health concerns connected to several PFAS and they do not degrade in the environment but contaminate food, feed and drinking water wherever they are used. There are many of them, with more than 4 700 substances listed as PFAS in the OECD’s Global Database, and they all have very high persistence as a common property. Even if we stopped manufacturing them tomorrow, they would still be around for generations as no other manufactured chemicals stay in the environment as long as PFAS. This is why PFAS are often called forever chemicals.

Where are PFAS found?

As mentioned, PFAS are used in many different products where they can add a variety of useful properties, for example, they are used in rain clothes to repel oil and water but they are also used in firefighting foams and fire protective clothing, non-stick coating for frying pans and pots, food packaging such as microwave popcorn bags and many fast food wrappings, cosmetic products, textiles for furniture, surface treatments on other textiles and carpets, paints, chrome plating, film covering solar panels, construction materials such as coatings on metals and tiles – to name a few.

How do PFAS affect your health?

The wide use of PFAS has had a serious effect on the environment already. Studies have shown that PFAS have contaminated drinking water and soils in Europe and the US, and a range of PFAS have been found in the blood of nearly all tested American citizens. PFAS are not new, they have been used since the 1940s, and as they don’t degrade, they have already had plenty of time to build up in the environment and some in humans and animals as well. The health concerns are serious. Tests have indicated that some PFAS cause effects such as raised cholesterol levels, weakened immune systems, kidney and testicular cancer and damage to the liver.

How can you avoid PFAS?

It is obviously not easy to completely avoid PFAS as the use of the substances is so widespread. You can be exposed to PFAS through food, drinking water, the clothes you wear, cosmetics and many of the other products mentioned above. There are still a few things you can do to reduce your exposure though. You can, for example, buy products with eco-labels or products that directly indicate that they are free of PFAS.

What is the EU doing about it?

The manufacture and use of some PFAS are already restricted as part of the EU’s chemicals legislation. Several EU Member States have proposed further restrictions of perfluorinated carboxylic acids that are identified as PFAS. ECHA’s scientific committees agree with these proposals and support the restriction.

Furthermore, ECHA and the European Commission are carrying out studies related to PFAS used in fire-fighting foams and textiles.

The REACH Candidate List of substances of very high concern (SVHCs) also contains several substances listed as PFAS. The Candidate List is the first step for controlling substances under the REACH authorisation process. It also triggers many companies to look for safer substitutes for the substances listed on it. Several more PFAS are under further evaluation and potential testing.

The use of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its derivatives (PFOS) and other substances categorised as PFAS are already restricted by the EU. Several EU Member States and Norway have proposed to restrict several other PFAS substances.

ECHA’s databases contain more than 2 000 individual PFAS that are on the EU market. Due to the large number of PFAS, ECHA has since 2014 assessed them in groups rather than one by one to speed up the process.

Podcast: How is the EU making sure PFAS chemicals don’t stick around?

Interview with Bjorn Hansen, ECHA's Executive Director about PFAS. Where are they used, what are the concerns and what is the EU doing about them?

Listen to the full podcast:

Read more

- Portal on Per and Poly Fluorinated Chemicals, OECD

- Emerging chemical risks in Europe — ‘PFAS’, European Environmental Agency

- PFAS public consultation: draft opinion explained, European Food Safety Agency

Infographic

Read Also

-

general

generalThe problem with microplastics

Plastics are important materials. They make our lives easier and are often lighter and cost less than alternative materials. However, if they are not properly disposed of or recycled, they can persist for long periods in the environment and can also degrade into small pieces that are of concern – microplastics.

READ MORE -

general

generalBisphenol A

Bisphenol A (BPA) has been on the market since the 60s. It is used in a wide range of consumer products such as plastic bottles and receipts. Due to its hazardous properties, BPA has already been restricted in several products in the EU.

READ MORE